Gifted With Specific Learning Disabilities (SLD)

Before we begin, we want to emphasize the importance of working with the specialists in your district or building. You cannot become an expert in giftedness nor specific learning disability (SLD) in a short course! Our purpose is to provide a common definition, understanding of characteristics, and a few strategies for the unique population of students who are gifted and have a SLD.

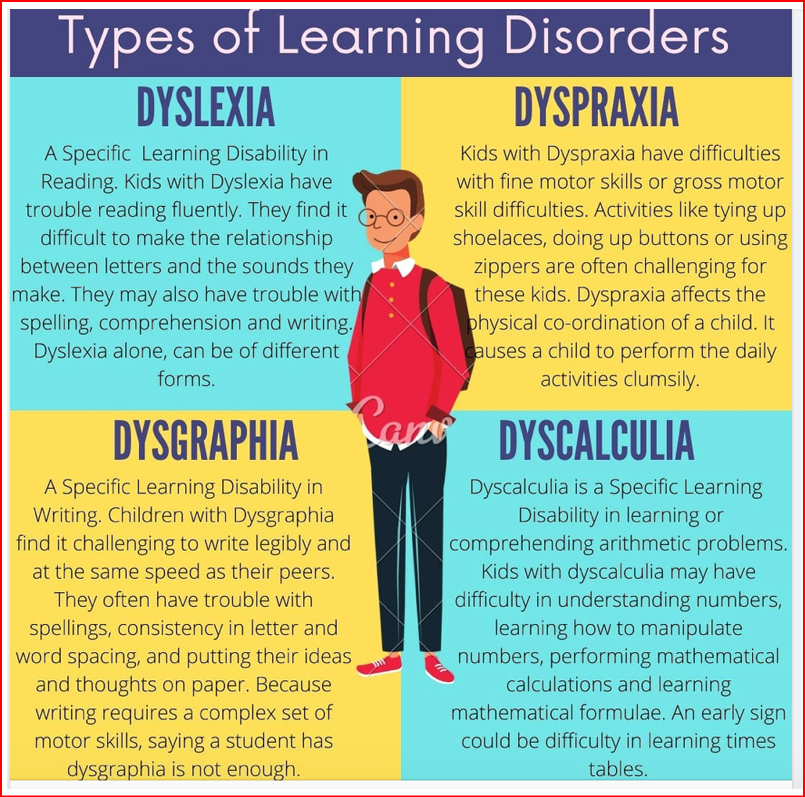

Many people think of dyslexia when they hear the term SLD, but dyslexia is only one possible specific learning disability (SLD); others include visual and auditory processing disorders (see picture below).

It is also important to remember that SLD can only diagnosed by a doctor or licensed psychologist. In the school setting a child is evaluated for a disability in reading, writing, or math. If they are identified (not diagnosed!) with one of these learning differences, they might or might not qualify for an IEP as it depends upon how impactful it is in the school setting. Because federal law changed in 2004, and Colorado law followed suit, many gifted students with dyslexia do not qualify for IEPs. In 1999, the law read that: "A team may determine that a child has a specific learning disability if – (1) The child does not achieve commensurate with his or her age and ability levels in one or more of the areas.... (34 C.F.R. §300.541). In 2006, the law dropped the phrase "and ability levels" and used age and grade-level achievement only: "The child does not achieve adequately for the child’s age or to meet state-approved grade- level standards in one or more of the following areas...." Many gifted students--who often do not fall significantly behind grade level because they are able to compensate for their dyslexia using their giftedness—are often very difficult to get a designation of SLD. But while they may not qualify for an IEP, they can be supported with a 504 plan. (For more explanation from CDE's Office of Special Education, you may select this optional webpage to read.)

Colorado Reading to Ensure Academic Development (READ) Act

Having a Significant Reading Deficiency is not the same as having a Specific Learning Disability. By definition, a student cannot be determined to have SLD if the student has simply had a lack of good instruction, but a student whose reading instruction has been poor might still have a significant reading deficiency and need a READ Plan. The READ Plan is meant to stay in place only while it is needed, until the student gets basic reading skills in place and can read at grade level.

The READ Plan is the way Colorado schools document what they are doing for each student and how well it is working. The plan follows a research-based process of specific diagnosis, goal-setting, progress monitoring, and evidence-based practice, including family involvement.

While it would not be typical for a gifted student with dyslexia to qualify for a read plan—again because of the ability to use higher-order thinking strategies to compensate and “hide” the disability, it is not impossible for a 2e student to fall behind enough to need this plan.

Identification Issues

Under-identification of gifted students with SLD often occurs because identification models are too insensitive for these students who often have strong compensatory mechanisms so never get screened or identified for instructional help (McCallum & Bell, 2013). Without identification, these students will not get the support they need.

Recommendations:

- Screen for reading, math, and writing deficits

- Screening probes should be multi-dimensional and include reading comprehension and math reasoning

- Look for students who score well above the mean in one area (reading, math, writing) but also have a significant discrepancy in one of the other areas

- When assessing for reading disabilities, make sure that the assessment tool is correlated to the actual area of reading in question. For example, a gifted elementary student whose teacher was convinced that she had a fluency problem was placed into an intervention centered around fluency. However, the student’s fluency failed to show any improvement. When the reading specialist assessed her, it was determined that she didn’t have a fluency issue; the student had perfectionistic tendencies. When perfectionism was addressed, her reading fluency increased.

We're going to take a brief look at specific learning disabilities. Several links are included for you to look deeper into areas of interest.

Dyslexia

For a 1:42 minute introduction to dyslexia from a strength-based approach, begin by watching the trailer for a movie HERE. Now that you have a brief, strength-based introduction, watch this more technical video on dyslexia by playing the

As with other learning disabilities, dyslexia is a lifelong challenge. This language-based processing disorder can hinder reading, writing, spelling, and sometimes even speaking. Dyslexia is not a sign of poor intelligence, laziness, or the result of impaired hearing or vision. Children and adults with dyslexia have a neurological disorder that causes their brains to process and interpret information differently (National Center or Learning Disabilities)

How Common is Dyslexia?

According to The International Dyslexia Association: 15-20% of the population has a language-based learning disability. Of the students with specific learning disabilities receiving special education services, 70-80% have reading deficits. Dyslexia affects males and females nearly equally as well as people from different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds. Children do NOT outgrow reading failure or dyslexia (National Institutes of Health Research).

Shaywitz (2003) neuroscientist, professor of pediatrics at Yale and co-director of Yale Center for the Study of Learning and Attention found that “Schools identify many more boys than girls; in contrast, when each child is tested (research identified) comparable numbers of boys and girls are identified as reading disabled” (p. 32). National Center for the Study of Adult Learning and Literacy stated that schools identify 4x as many boys as girls because externalizing behavioral characteristics are more likely to bring boys to teachers’ attention (www.ncsall.net).

Regardless of high or low overall scores on an IQ test, children with dyslexia show similar patterns of brain activity, and the use of “whole language” method is not an effective way to teach dyslexic children to read. Because the READ Act requires CDE to identify quality reading instructional programs, they have created a list of approved reading and intervention programs. You can find this list HERE.

According to National Institutes of Health Research (NIH) dyslexia is the leading cause of reading failure and drop-outs, and is identifiable with 92% accuracy at ages 5½-6½ with early intervention being essential for school success. Dyslexia and ADHD frequently coexist. Dyslexia Warning Signs at Different Ages from Preschool through High School are outlined in this article. (Optional reading, see also: Understood.org "what you're Seeing in Your High Schooler" and "What you're Seeing in Your Preschooler.")

One sign above to note with concerning 2e learners is that often gifted and/or bright students with dyslexia will read complex words while missing easier words especially when these complex words reflect their interests – these students memorize these words that reflect their passions or infer them from context clues.

Remember the Strengths:

While the idea that dyslexia could be a positive learning difference angers some who face the hardships that come with this difference, Drs. Brock and Fernette Eide (2012) have been studying the neuroscience of learning differences by studying brain patterns and believe that there is a growing amount of evidence that supports that there is a “dyslexic advantage.” They believe that the dyslexic brain is a “reflection of a different pattern of brain organization and information processing --one that predisposes a person to important abilities along with the well-known challenges” (Dyslexic Advantage, p. 4). They say that “For dyslexic brains, excellent function typically means traits like

- the ability to see the gist or essence of things or to spot the larger context behind a given situation or idea;

- multidimensionality of perspective;

- the ability to see new, unusual, or distant connections;

- inferential reasoning and ambiguity detection;

- the ability to recombine things in novel ways and a general inventiveness;

- and greater mindfulness and intentionality during tasks that others take for granted.” ( p. 42)

They also say that some strengths that come with dyslexia are spatial reasoning & mechanical ability (engineering, art, entrepreneurship) and relationships such as analogies, metaphors, paradoxes, similarities, differences, so, while many SLD specialists object to the narrative in gifted education circles about the “gift of dyslexia,” perhaps we can acknowledge the tremendous struggles involved in this neurological difference while still giving students hope and awareness of successful dyslexics.

To reinforce this strength-based perspective, watch this 4:05 minute video:

Dysgraphia

Dysgraphia is “A learning disability that affects writing, which requires a complex set of motor and information processing skills. It can lead to problems with spelling, poor handwriting and putting thoughts on paper” (National Center for Learning Disabilities)

Begin by watching this 2:04 video below. There are no subtitles because everything is written with music in the background.

Signs and Impact

Dr. Sheldon Horowitz (National Center for Learning Disabilities) says that dysgraphia involves three areas that can impact a child’s ability to write:

Visual-Spatial Difficulties: Has trouble with shape-discrimination and letter spacing; Has trouble organizing words on the page from left to right; Writes letters that go in all directions, and letters and words that run together on the page; Has a hard time writing on a line and inside margins; Has trouble reading maps, drawing or reproducing a shape; Copies text slowly.Fine Motor Difficulties: Has trouble holding a pencil correctly, tracing, cutting food, tying shoes, doing puzzles, texting and keyboarding; Is unable to use scissors well or to color inside the lines; Holds his wrist, arm, body or paper in an awkward position when writing.

Language Processing Issues: Has trouble getting ideas down on paper quickly; Has trouble understanding the rules of games; has a hard time following directions; Loses his train of thought.

Erica Patino describes characteristics of dysgraphia this way: (Understood.org )

Spelling Issues/Handwriting Issues: Has a hard time understanding spelling rules; has trouble telling if a word is misspelled; can spell correctly orally but makes spelling errors in writing; spells words incorrectly and in many different ways; has trouble using spell-check—and when he does, he doesn’t recognize the correct word; mixes upper- and lowercase letters; blends printing and cursive; has trouble reading his own writing; Avoids writing; gets a tired or cramped handed when he writes; erases a lot.

Grammar and Usage Problems: Doesn’t know how to use punctuation; overuses commas and mixes up verb tenses; doesn’t start sentences with a capital letter; doesn’t write in complete sentences but writes in a list format; writes sentences that “run on forever.”

Organization of Written Language: Has trouble telling a story and may start in the middle; leaves out important facts and details, or provides too much information; assumes others know what he’s talking about; uses vague descriptions; writes jumbled sentences; never gets to the point, or makes the same point over and over; is better at conveying ideas when speaking.

Note: Put signs for dyslexia, dysgraphia and dyscalculia in folder for class. Also the link currently in the class does not have the specific information for the signs of dysgraphia.

Dyscalculia

Dyscalculia is a learning disability in math. People with dyscalculia struggle with math on many levels. They often struggle with key concepts like bigger vs. smaller. And they can often have a hard time doing basic math problems and more abstract math. Understood: What is Dyscalculia?

To begin watch this video: What is dyscalculia

Some resources to consider are the Understood Article: What is Dyscalculia? and the website dyscalculia.org provides multiple resources including classroom supports and sample checklists.

The following links provide information for signs of dyscalculia at different ages:

- Dyscalculia in Preschool: 4 Signs You Might See

- Dyscalculia in Grade School: 4 Signs You Might See

- Dyscalculia in Middle School: 4 Signs You Might See

- Dyscalculia in High School: 4 Signs You Might See

Dyspraxia

Dyspraxia is a term that refers to lifelong trouble with movement and coordination. It’s not a formal diagnosis. But you may still hear people use this term, especially in the U.K. The formal diagnosis is

developmental coordination disorder

(DCD). Understood: What is Dyspraxia?

The video on Developmental Coordination Disorder: One of the "Other" Twice Exceptionalities is optional. Although almost an hour long, it is provides very detailed information that relates specifically to twice exceptional learners. It also raises the need to have more concise information available on the relationship with DCD and ADHD. Case studies of a 2e/3e students with dyspraxia presented at the 20:00 minute point in the video provide real life data and video observations.