Mental and Behavioral Health

| Sitio: | Colorado Education Learning Management System |

| Curso: | 2e (Open Access) Supporting Twice Exceptional Learners |

| Libro: | Mental and Behavioral Health |

| Impreso por: | Invitado |

| Fecha: | jueves, 5 de febrero de 2026, 05:36 |

Descripción

SpEd licensing note: behavioral health training that is culturally responsive and trauma- and evidence-informed, which may include:

- mental health first aid training, specific to youth and teens

- training modules concerning teen suicide prevention

- training on interconnected systems framework for positive behavioral interventions and supports and mental health

- training approved or provided by the school district where the teacher is employed

- training modules concerning child traumatic stress

Tabla de Contenidos

- 1. Children's Mental Health - Schools' Important Role

- 2. Social/Emotional/Behavioral Practices

- 3. Finding the root cause of behavior

- 4. Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP)

- 5. Trauma

- 6. Utilizing MTSS for support

- 7. What is culturally responsive teaching?

- 8. Optional Resources

1. Children's Mental Health - Schools' Important Role

The National Center on Safe Supportive Learning Environments writes that,

Mental health is an important part of overall student well-being. While typically about 20% of children and youth experience a mental, emotional, or behavioral disorder, only about half that many receive mental health services (NASP, 2020; Bradshaw et.al, 2020). Of those who do receive mental health services, 60-80% receive them in schools (Green et al., 2013). Schools are therefore uniquely positioned to have a significant impact on student mental health and well-being [emphasis added].…it is important to revisit the key components of a complete school mental health program. A comprehensive approach must include: awareness and surveillance of mental health needs; crisis support and early intervention; screening and early detection; treatment and support; follow-up and aftercare. Thoughtful planning, training, implementation, and policy development to ensure sustainability are needed for districts to implement comprehensive systems to address the needs of their student populations. (ncssle@air.org email May 31, 2021)

Two other resources (optional, perhaps bookmark for later)

This site shares a plethora of resources that are designed to help teachers and administrators support student's mental health. Resources include modules related to mental health screening, as well as information on how to develop a business plan to make mental health services sustainable. Note: To access the resource, one must provide information to the federally-funded technical assistance center that developed it.

2. Social/Emotional/Behavioral Practices

IDEA regulations define “specially designed instruction”(SDI) as “adapting, as appropriate to the needs of an eligible child under this part, the content, methodology or delivery of instruction

- (i) to address the unique needs of the child that result from the child’s disability; and

- (ii) ensure access of the child to the general curriculum, so that the child can meet the educational standards within the jurisdiction of the public agency that apply to all children.” (34 CFR Sec. 300.39(b)(3)

When creating SDI, special educators use high-leverage practices (HLP), intensive instruction, and consideration of learner characteristics.

What are HLPs?

The Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability and Reform (CEEDAR) and the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) developed and published a set of high-leverage practices for special educators and teachers to use with specifically designed instruction. The HLPs are organized around four aspects:

While these practices can help all students, they are especially important for our students with disabilities. Within the domain of social/emotional/behavioral practice are 4 HLPs. (Credit for below: HLP for Students with Disabilities)

1) Establish a consistent, organized and respectful learning environment

When establishing learning environments, teachers should build mutually respectful relationships with students and engage them in setting the classroom climate (e.g., rules and routines); be respectful; and value ethnic, cultural, contextual, and linguistic diversity to foster student engagement across learning environments.

2) Provide positive and constructive feedback to guide students' learning and behavior

Feedback may be verbal, nonverbal, or written, and should be timely, contingent, genuine, meaningful, age appropriate, and at rates commensurate with task and phase of learning (i.e., acquisition, fluency, maintenance).

3) Teach social behaviors

Teachers should explicitly teach appropriate interpersonal skills, including communication, and self-management, aligning lessons with classroom and schoolwide expectations for student behavior.

4) Conduct functional behavioral assessments to develop individual student behavior support plans (for students' who need extra support)

Key to successful plans is to conduct a functional behavioral assessment (FBA) any time behavior is chronic, intense, or impedes learning.

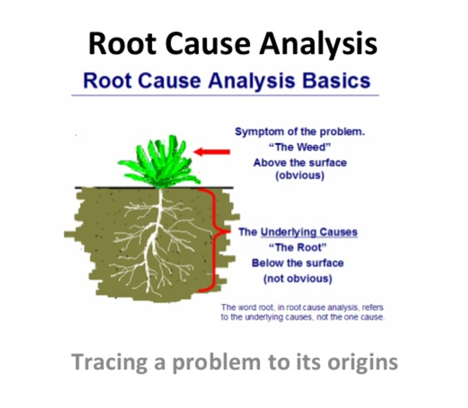

3. Finding the root cause of behavior

When examining behavior or mental health supports, all of the students exceptionalities should be taken into consideration.When a student is presenting with unexplained behaviors, it is imperative to dig down and find the root cause. Often times 2e students' strengths or disabilities are masked, and they can become frustrated and act-out or withdraw.

Twice-exceptional students may also have additional factors such as trauma. It is also It is important to find out the source of the behavior and not make assumptions.

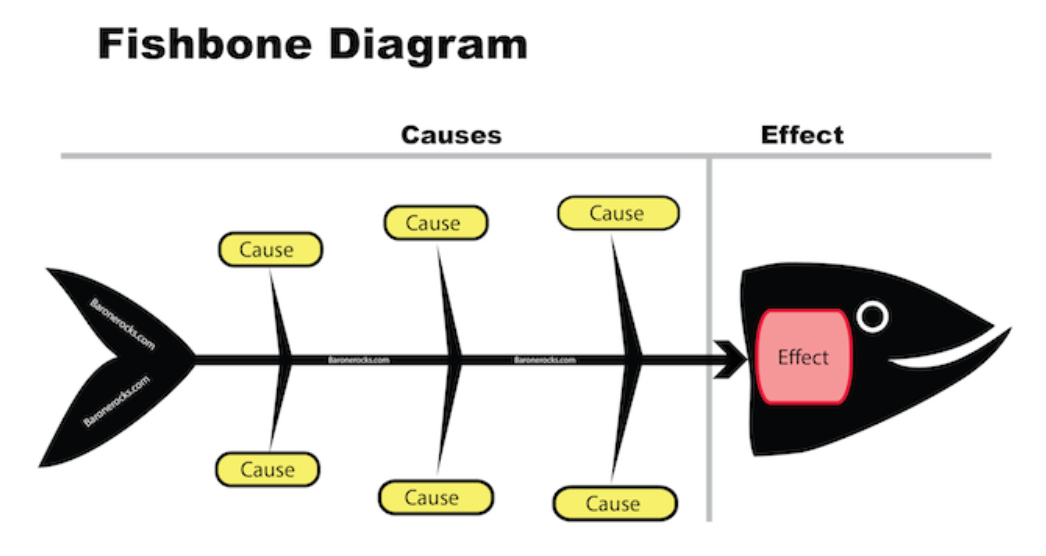

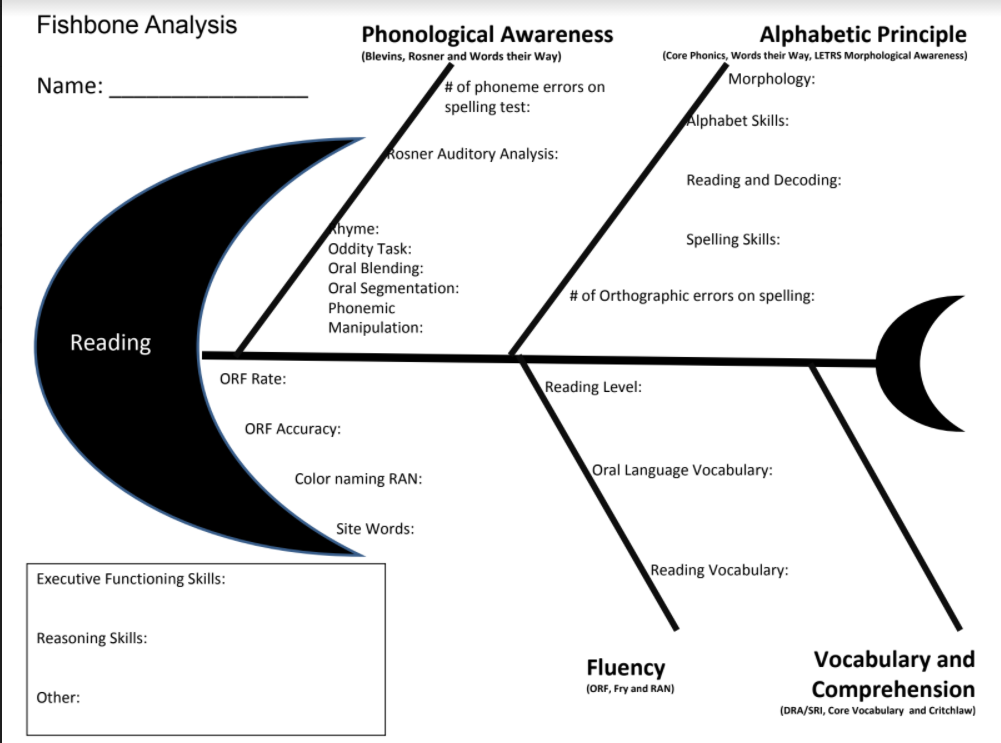

Fish bone analysis helps many educators with this process. This analysis is:

A cause and effect diagram, often called a “fishbone” diagram, can help in brainstorming to identify possible causes of a problem and in sorting ideas into useful categories. A fishbone diagram is a visual way to look at cause and effect. It is a more structured approach than some other tools available for brainstorming causes of a problem (e.g., the Five Whys tool). The problem or effect is displayed at the head or mouth of the fish. Possible contributing causes are listed on the smaller “bones” under various cause categories. A fishbone diagram can be helpful in identifying possible causes for a problem that might not otherwise be considered by directing the team to look at the categories and think of alternative causes. Include team members who have personal knowledge of the processes and systems involved in the problem or event to be investigated. (CMS.gov)

Below is one template for this analysis and below the template is an exemplar. For more information (optional), there is a document with directions and other exemplars in our Google folder.

Another, formal and often essential, way to find the root cause of behavior is to do a Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) explained in the next chapter.

4. Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) and Behavior Intervention Plans (BIP)

What is a functional behavioral assessment (FBA)?

"A functional behavioral assessment (FBA) can be a helpful tool as you work through the process of gathering information about behaviors of concern, whether the behaviors are academic, social or emotional....

FBAs are appropriate for use at all three tiers of multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), but are often used in Tier 3 with students requiring individualized behavioral support....FBAs have also been shown to be an effective with a broad range of populations and in a variety of educational settings.

FBAs are rooted in the theory that behavior is functional (meaning it has a purpose), predictable and changeable1. Understanding the function or purpose underlying a student’s behavior can help a school team develop a plan to teach the child more appropriate replacement behaviors for a setting or provide support for the development of more desirable behaviors.

FBAs should provide the team with the following information:

what the challenging behavior is in observable and measurable terms, and where, when, and with whom the behavior occurs;

what the antecedents are (what typically occurs before the behavior);

what consequences reinforce or maintain the behavior (what typically occurs after the behavior);

what interventions and strategies have been tried previously and their effects; and

what the setting events are (what makes the problem behavior worse or more likely to occur).

5. Trauma

We often talk about students who are "at risk" but Dr. Hendershott emphasizes that many students are beyond at risk; they are already wounded--with 60% of students, pre-COVID 19, dealing with trauma (Courage to Risk, 2021).

Trauma is defined as "a response to an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being (SAMHSA, 2014).

Examples of trauma students may have--or are experiencing--include abuse, neglect, witnessing violence, poverty, loss, etc. Poverty and loss of parents does not necessarily mean a student is wounded, but it may because of the long term duress caused by severe stress. Researchers have also identified historical trauma -- a constellation of characteristics associated with massive cumulative group trauma across generations (such as Native- and African-Americans).

Trauma can affect a person’s physical and emotional health. Students who experience high levels of trauma may have physiological changes in brain development that can cause difficulties in memory, emotional regulation, and problem solving skills (Medical News Today).

The primary impact of exposure to trauma is “emotional dysregulation” (Van der Kolk, 2009).

In the field of trauma, experts say that challenging behaviors must be seen as communication (even if it is misguided and ineffective communication until a wise person begins to understand it).

Some indicators that a child might be experiencing trauma are characteristics of fight or flight, e.g., anger, aggression, withdrawal, disconnected, and/or depression (Hendershott). Below is a chart of behaviors that may manifest as a result of trauma (credit: Bill Brown, Courage to Risk, 2021).

Hyper-arousal – Increase in tension, anxiety, panic, rage, exaggeration of startle responses |

Hypo-arousal: - Decrease in tension, including emotional indifference, depression, hopelessness, irritability |

|---|---|

Inability to sit still Inability to focus Agitated Argumentative Impulsive actions Pacing Tense shoulders/muscles Angry outbursts Sleep troubles Quick to lose temper Racing thoughts Running from the situation |

Defiant Withdrawn Tardy Absent Shuts down Avoids tasks Forgetful Attitude of not caring Lack of response Poor memory Sleepiness/feeling tired Brain fog |

A highly traumatized student is often flooded with the hormone cortisol and centered in limbic/amygdala-guided responses. When in this survival mode, the student will be hypervigilant to danger and even mistake normal cues as dangerous. They may also manifest false beliefs (i.e., "I'm no good; I'm dumb") which leads to emotional upheaval and dysfunctional behavior (Hendershott). Heather Forbes (credit: Bill Brown, CDE) notes that traumatized individuals often project their pain, and other negative emotions, onto you, for example, they say "you're stupid" when they mean "I feel stupid." They often argue because agitation is the state they are most familiar with and lack motivation because they are already overwhelmed just surviving. They feel themselves so far from a compliment, that they will argue against it (unless you say you like something from your perspective, such as "I like your shirt"). They are always interpreting the world through the lens of fear.

Since the emotional center of our brain doesn't tell time, a current event can trigger trauma from a past event hurling a student back to that time when the trauma first happened (Heather Forbes). As educators, it is helpful to know what traumatized students' triggers are (build relationships!), and if you suspect there has been a triggering event, don't ask why they did something, but instead keep your distance and ask "What's going on, or how can I help?" (Dr. Hendershott). Creating calm and a sense of safety is the first step to reaching a triggered student.

Trauma Informed Practices

It takes relationship building to begin to make a difference in traumatized students' lives. In fact, supportive relationships before, during, or after trauma help mitigate the risks associated with trauma. As Herschell Hargrave (2010) says, "Trauma is like no other experience. We cannot talk children out of it, or discipline them into appropriate behaviors. Consequences never change a person on the inside."

What does NOT work (often our go-to strategies because we are operating from our frontal cortex, but the traumatized student is in the survival brain):

•Time-out

It is always hard when conflict arises, but if you can stop and think, "How can I make this student feel safe," you can take a step toward building a relationship and making a difference for a traumatized student. It is only connection that will make a difference.

Effective trauma informed practices align well with social emotional learning (SEL) and Positive Behavior Intervention Supports

(PBIS) creating a continuum of interventions and positive classroom

environments (Bill Brown, Courage to Risk, 2021). Your school/district MTSS framework should be helpful in understanding and planning for traumatized students.

Prioritize relationships and students' sense of

- physical and emotional safety

- trust

- choice and control (empowerment--the opposite of the powerless which was foundational to the trauma)

- resiliency

We act according to what we believe and feel. Helping students change their beliefs and feelings--their mindsets--will be a slow process--resetting the limbic system isn't easy or quick, but changing their fearful and defensive thinking through successful new experiences will help change their lives. Keep in mind that they might not even know what contentment, happiness, and joy looks like and might not have ever experienced what it feels like.

If you can take a system's perspective (and that can be a classroom, school, or district) you can help:

1. create

a safe, predictable, positive environment

2. build

the capacity of students, staff, and families

3. support

all students using child-centered strategies that are matched to needs.

4. partner with families and the community

5. invest

in practices that promote community and dignity of all

6. develop instructional discipline policies that emphasizes restoration over punishment (adapted from Samsa by Bill Brown)

If your building has a lot of need, your school might consider using Cognitive Behavior Intervention for Trauma in Schools, but there is a cost.

Ross Greene has helped us understand that all students want to do well, and we should start with "they would if they could." We should seek to understand what skill sets are missing and how to teach these skills. It is helpful to shift your mindset from what is wrong with this student to "what has happened to this student." Try to enter the students' reality--not even showing sympathy or contradicting a student's negative statement about themselves before understanding their perspective; ask questions first (Heather Forbes).

Some schools have found that teaching empathy and replacing suspensions with community service or restorative justice has reduced infractions and drop-out rates. It is not, however, just students who need to develop empathy; with the staggering statistics of how many traumatized students we now have, and how important relationships are to changing their futures, we as educators need to find ways to increase and develop our own empathy to ensure we are creating respectful, safe, learning environments.

For more resources (optional), see our Google folder links under trauma.

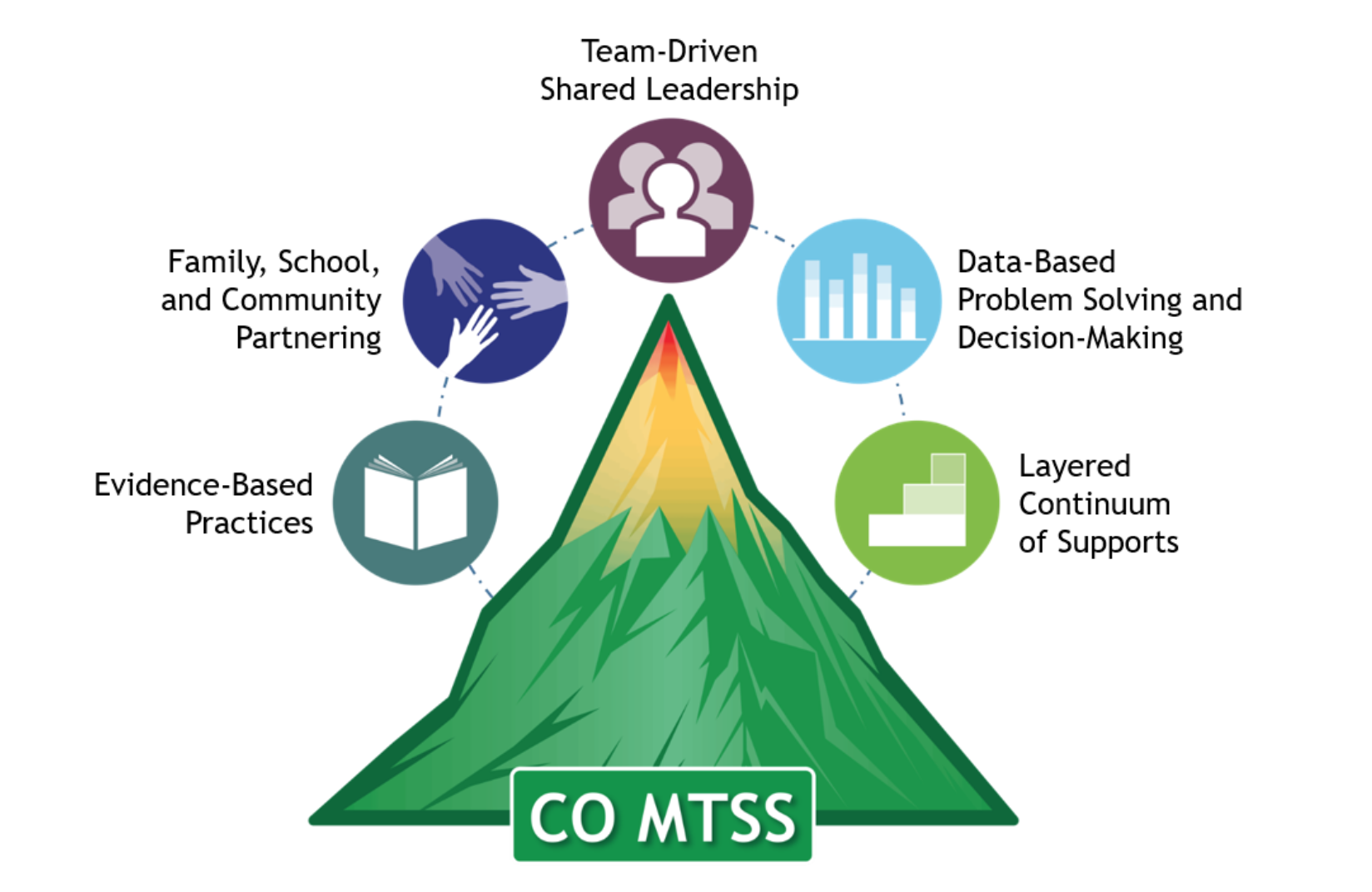

6. Utilizing MTSS for support

- MTSS is a good forum to discuss and plan how you will support twice-exceptional and students with mental health needs.

7. What is culturally responsive teaching?

The following is from a post by Kristin Burnham (Northeastern University, 2020) on "5 Culturally Responsive Teaching Strategies"

What is culturally responsive teaching?

Culturally responsive teaching, also called culturally relevant teaching, is a pedagogy that recognizes the importance of including students’ cultural references in all aspects of learning....

“Teachers have more diverse classrooms today. We don’t have students sitting in front of us with the same background or experience, so instruction has to be different,” she says. “It needs to build on individual and cultural experiences and their prior knowledge. It needs to be justice-oriented and reflect the social context we’re in now. That’s what we mean when we talk about culturally responsive teaching.”

Culturally Responsive vs. Traditional Teaching Methods

Culturally responsive teaching can manifest in a number of ways. Using traditional teaching methods, educators may default to teaching literature by widely accepted classic authors: William Shakespeare, J.D. Salinger, and Charles Dickens, for example, adhering to widely accepted interpretations of the text.

Culturally responsive teaching, on the other hand, acknowledges that there’s nothing wrong with traditional texts, Childers-McKee says, but strives to include literature from other cultures, parts of the world, and by diverse authors. It also focuses on finding a “hook and anchor” to help draw students into the content using their past experiences.

“This way, students can see themselves in some of what they’re reading and not just the white, western world. The learning is more experimental, more hands-on,” she says. “Instead, you’re showing them a worldwide, multicultural community and looking for different interpretations while relating it to what it means for society today.”

Why is culturally responsive teaching important?

....Childers-McKee says...“That typical, mainstream education is not addressing the realities of today’s students. Culturally responsive teaching isn’t just for those students who don’t come from white, middle-class, English-speaking families—it’s an important teaching strategy for everyone. When done the right way, it can be transformative.”

When integrated into classroom instruction, culturally responsive strategies can have important benefits such as:

1. Strengthening students’ sense of identity

2. Promoting equity & inclusivity in the classroom

3. Engaging students in the course material

4. Supporting critical thinking

Here’s a look at five culturally responsive teaching strategies all educators can employ in their classrooms.

5 Culturally Responsive Teaching Strategies for Educators

1. Activate students’ prior knowledge.

Students are not blank slates, Childers-McKee says; they enter the classroom with diverse experiences. Teachers should encourage students to draw on their prior knowledge in order to contribute to group discussions, which provides an anchor to learning. Taking a different approach to the literature that’s taught in classrooms is one example of this.

2. Make learning contextual.

Tie lessons from the curriculum to the students’ social communities to make it more contextual and relevant, Childers-McKee advises. “If you’re reading a chapter in history class, for example, discuss why it matters today, in your school, or in your community,” she says. “Take the concept you’re learning about and create a project that enables them to draw parallels.”

3. Encourage students to leverage their cultural capital.

Because not all students come from the same background, it’s important to encourage those who don’t to have a voice. Say, for example, you teach an English class that contains ESL students. It’s important to find ways to activate the experiences they do have—their cultural capital, Childers-McKee says.

The teacher may choose a book for the class to read in which the ESL students could relate and feel like they could be the expert, for instance. As a teacher, Childers-Mckee’s once chose a book that told the story of a child of migrant workers because some of her students came from an agricultural background.

“When you have a mixed classroom, you want those in the minority to feel like they are an expert. You want to draw from their experiences,” she says. “I do caution that you don’t want to cross a line and make ‘Johnny’ feel like he needs to speak for all Mexican people by putting them on the spot, for example. That’s a line you need to walk.”

4. Reconsider your classroom setup.

Take inventory of the books in your classroom library: Do they include authors of diverse races? Is the LGBTQ community represented? Do the books include urban families or only suburban families? Beyond your classroom library, consider the posters you display on your walls and your bulletin boards, too. “These are all small changes you can make to your classroom more culturally responsive,” Childers-McKee says.

5. Build relationships.

Not all students want to learn from all teachers because the teachers may not make them feel like they’re valued, Childers-McKee says. Teachers need to work to build relationships with their students to ensure they feel respected, valued, and seen for who they are. Building those relationships helps them build community within the classroom and with each other, which is extremely important, she says.

“When we think about culture and diversity, people often automatically think about black students, but people need to think broader than that, now,” Childers-McKee says. “Some teachers whose students are all white and middle-class struggle with how culturally responsive teaching strategies apply to them. It’s equally important for them to teach students about diversity. These aren’t just teaching strategies for minorities, they’re good teaching strategies for everyone.”